The Education and Urbanism of Breaking Away

From limestone quarries to the National Championship: How this 1979 film captures the evolution of Indiana University, Bloomington, and the classic American college town.

Note: This article is part of my Education & Urbanism series. You can see previous editions with Dazed & Confused and King of the Hill.

Indiana University (IU) has made a historic run in college football, going from one of the worst teams in the sport to winning the National Championship. In recognition of this Cinderella turnaround, I wanted to write about a classic homage to the university with the movie Breaking Away (1979).

I’ve had Breaking Away on my list of movies to write about since I started College Towns. The film is a classic college town tale that won an Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay in 1979. The life depicted in 1970s Bloomington, Indiana, can tell us a lot about the history of higher education, urbanism, and broader societal change in the US.

Note: If you are unfamiliar with Breaking Away, sorry, I may have to spoil this 47-year-old movie. But I think you can still read the article for insight into urbanism and higher education (the niche here at College Towns). It was directed by Peter Yates, and stars Dennis Christopher, Dennis Quaid, Daniel Stern, Jackie Earle Haley, Barbara Barrie, Paul Dooley, and Robyn Douglass.

The story centers on a group of friends from Bloomington, Indiana, who recently graduated from high school and are longing for what is next in life. One in the group, Dave, is obsessed with cycling and Italian culture. The crew ends up fighting with IU frat boys, and the president invites them to enter the annual Little 500 race. Given Dave’s cycling prowess, the locals end up winning. All based on a true story, too!

Becoming a Classic College Town

Breaking Away is essentially a movie about the town vs. gown relationship in a classic college town. Indiana University is central to Bloomington and all of Monroe County. Today, about 80,000 people live in Bloomington, while the university has an enrollment of around 48,000 students. Another some-odd 21,000 work for IU. In short, the university dominates the town’s population, civic culture, and economy, but it wasn’t always this simple.

Indiana had long been a strong mining state, with the area around Bloomington dubbed the “Limestone Capital of the World.” This mining sector provided stable and well-paying jobs to blue-collar workers in the state. Stone from Indiana quarries was used in state capitals, colleges, and other iconic structures from around the country, including at IU, as depicted in the film and with the townies dubbed Cutters.

By the late 1970s, though, these quarries began to shutter as the country began its long deindustrialization. Jobs were lost and regions like the Rust Belt dilapidated. Yet this kind of spiral did not happen in a place like Bloomington. Instead, the growth of IU bolstered the town and the surrounding area, a development style sometimes called Eds and Meds.

The more white-collar careers at the university replaced the old blue-collar workers of the quarries. This transition is the central struggle in Breaking Away. The fathers of all the boys in the crew had lost their jobs. The boys themselves had nothing but the service sector to fall back on. Despite Bloomington being their home, they felt alienated by the college and the community, which was only growing and encroaching on blue-collar Bloomington. The frat boys diving into the old quarry swimming hole is a visceral illustration of the takeover.

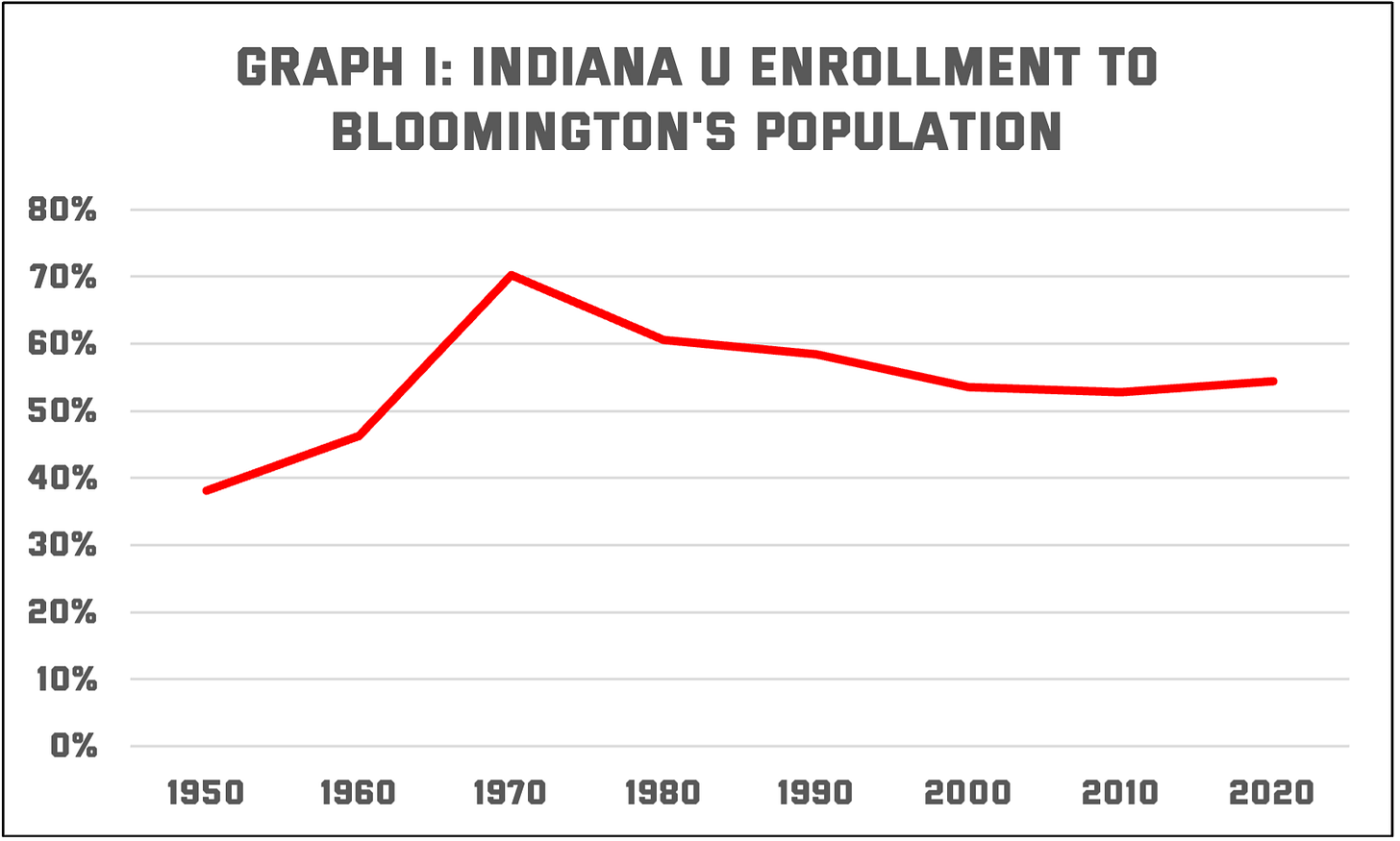

The time period of the film was part of a massive boom in US higher education enrollment, including at IU. From 1950 to 1970, the school tripled its student body, going from 10,715 to 31,877, peaking as a percent of the town’s population then (see Graph I). Although, only about 20% of American students went on to college then. Bloomington itself was growing as a city, with just over 28,000 residents at the start of that period, tripling to over 52,000 by 1980, including several land annexations.

Bloomington’s growth was coming from the expanded university staff and the various service sectors around campus. Not every blue-collar worker could transition, sending them looking for work in other parts of the country. They were replaced by a more educated workforce. It’s not that there are zero working-class people in Bloomington now, but the town and gown divide today is more about affluent landowners or retirees annoyed by loud students rather than split along class divides.

Breaking Away's depiction of the college looming over the town, slowly engulfing all civic, economic, and social aspects was real. The Cutters faded and Bloomington became a classic college town.

Little 500 and Vehicular Cycling

Breaking Away is certainly a bike movie. One of the few bike movies! But the biking in the film is not what most urbanists revere. Instead, what is depicted is mostly akin to a hobbyist activity, with the big race as the finale. Yes, the frat bros race in the Little 500, sure, but they also drive around town when they aren’t training.

Biking is actually portrayed as kind of a weird thing in Breaking Away. No one bikes around the college town for transport, except for the weird kid who fakes being Italian. In the end, the dad does adopt his son’s hobby, but it is played more for laughs. After all, this is the state that is home to the Indy 500.

The character who does bike around town is essentially a vehicular cyclist, à la John Forester. Just like vehicular cycling in real life, Dave is bold and aggressive on his bike, but his style is obviously dangerous. Early in the film, he chases down a girl on his bike through the campus area, darting across traffic and pedestrians. At one point, his dad almost smashes into him when he runs a red light. Dave even bikes down a freeway at one point, racing a semi-truck.

Bikes are simply an afterthought in the auto-centric world of 1978. His dad sells used cars, one friend (very) briefly works at a car wash, and both townies and frat bro crews are always cruising. There are no bike lanes or other infrastructure that we might associate with a good biking culture today.

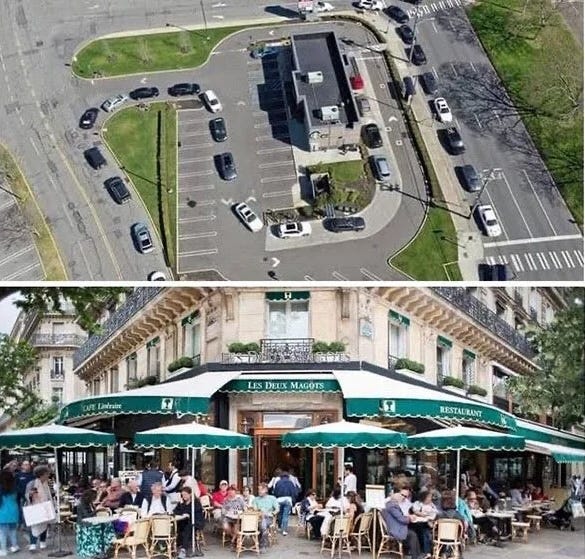

Many college towns across the country have better urbanism for walking, public transit, and biking. Not being as auto-centric as typical American suburban sprawl is one reason why people love college towns. Bloomington certainly fits the bill today. It is now one of the top small cities in terms of biking or walking to work. The town has built a network of bike lanes. IU has a strong bike culture that goes beyond just the hobby.

Italian Foreignness

Steve Tesich, the screenwriter, based Breaking Away on his time as a student at IU in the 1960s. Tesich’s experience highlights just how much ethnic perceptions have changed since the Boomers were in college. By the late 1970s, much of the post-War White ethnic homogenization was already in full swing, if not mostly complete. The film shows the residue of the enclave culture that defined US ethnic lines before the suburbanization efforts that really boomed in the 1950s.

Perhaps the film’s depiction of distrust in Catholicism and related ethnicities was overexaggerated by the time of filming. But these were real experiences and sentiments in the US at one point, which did not just disappear until several generations of the suburbanization that forced the various ethnicities out of their tight urban enclaves. It reflected the time of WASPs with different sensibilities.

Dad: What is this?

Mom: It’s sauteed zucchini.

Dad: It’s I-ty food. I don’t want no I-ty food.

Mom: It’s not. I got it at the A&P. It’s like... squash.

Dad: I know I-ty food when I hear it! It’s all them “eenie” foods... zucchini... and linguine... and fettuccine. I want some American food, dammit!

It seems incomprehensible that the dad would be unfamiliar with Italian food. But the father was roughly a Greatest or Silent Gen (the actor Paul Dooley was born in 1928!), meaning he grew up in an America before Italian food had become our national staple.

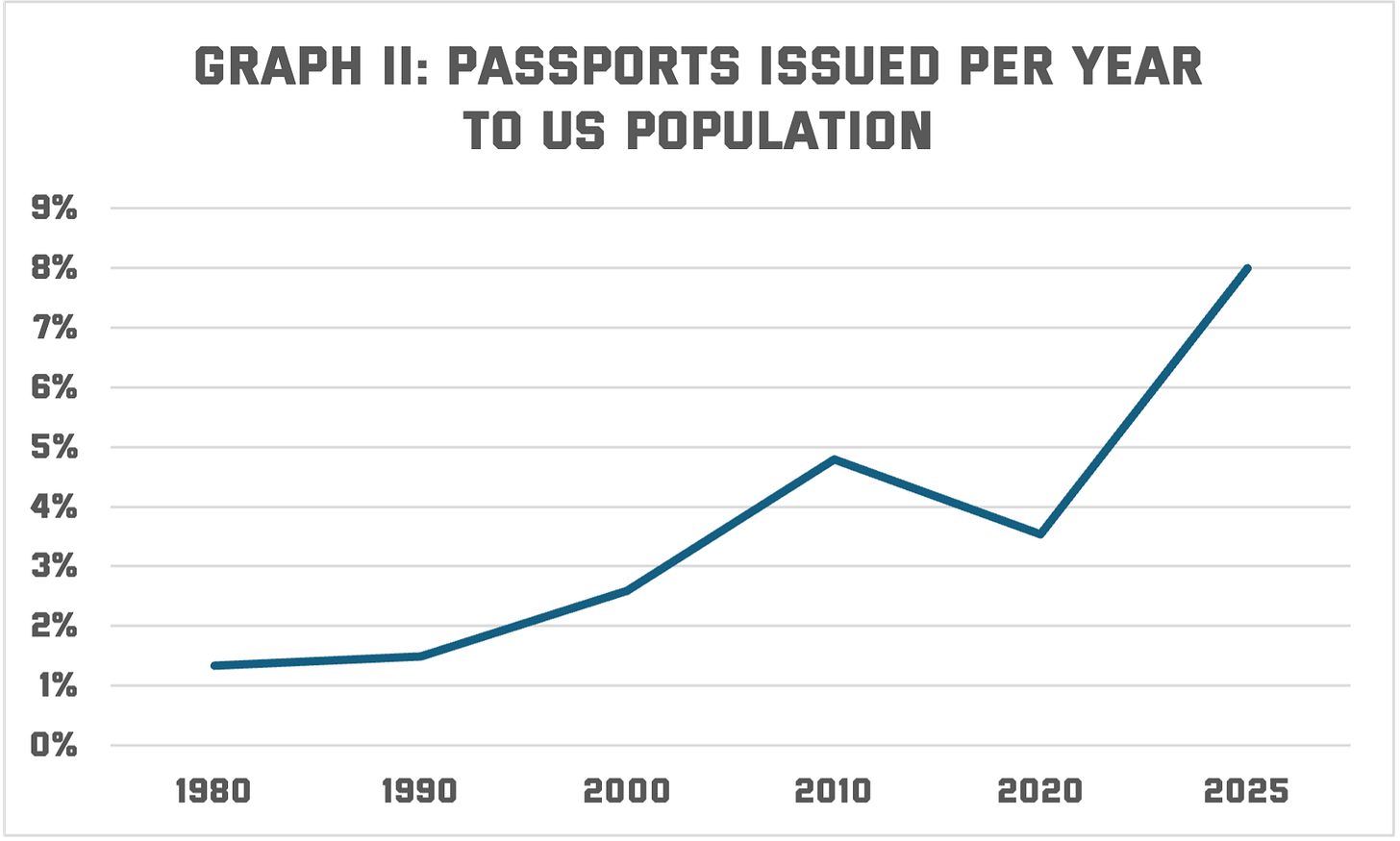

Few Americans had passports during this time, and certainly fewer studied abroad. Going to Italy would be reserved for the wealthy, as depicted in the film with the sorority girl. Dave’s mom having a passport would have been rare, so it perhaps makes sense that he himself was a little odd. His dad represented a more traditional working-class America, where going abroad, even to Europe, would have felt very alien when only a fraction of Americans applied for passports each year (see Graph II).

One idea that stuck out to me from the film was that Italy was poor. “Italians are all poor but they’re happy,” said Dave. This was well before the recent Europoor meme war that has gone around in the US recently. Yet at the same time, there was awareness that they were happy, driven by family, community, and structure, just like the memes about their urbanism today, too.

Pop culture is a whisper of our history. Memories. The screenwriter, who was born in Nazi-controlled Yugoslavia and immigrated to the US after the war, likely felt animosities targeted at non-WASP ethnics like himself, even as these have eventually faded. Likewise, Americans are similarly aware of how different Italy is compared to here; only now it’s more common to yearn for that lifestyle abroad, unlike with Breaking Away’s outcast protagonist.

The Checkered Flag

Breaking Away is often called a coming-of-age story. The boys in the town were portrayed as losers before winning that final Little 500 race. Yet they were different from the conception of losers today, typified by the modern incel concept (sitting in the basement, no outside hobbies but Internet posting, no friends, no romantic prospects). The loser of 1979 Bloomington was depicted as having a group of friends (the Cutters), who had a hobby (cycling), a romantic interest (sorority girl), and an intellectual pursuit (studying Italian).

The boy in real life who inspired the story did make good; Dave Blase raced, gained celebrity, graduated college, went abroad, and eventually became a teacher. He and his lore will forever be legendary in Indiana, where the Little 500 has remained a raucous tradition.

I was lucky enough to attend the festivities back in the late 2000s (see video above). Though not at the race itself, the campus was absolutely bonkers. That experience always made me wonder why more students didn’t clamor to attend the university. It’s a beautiful campus, in a fun college town, with exciting traditions, yet IU’s admission rate has long hovered around 70-80%. Given the recent trend of college applicants looking South, I wonder if the recent success by the school’s football team will start to juice those admission rates.

As Indiana University added a College Football National Championship in 2026, Breaking Away lives on as a real story change in Bloomington and broader America. Even IU being in the game itself represents vacillating changes in wealth dynamics between various regions, just as the blue-collar stonecutters got pushed out by white-collar university workers before. IU has now pushed out former dominant schools with new money.

The team’s star quarterback, Fernando Mendoza, won the Heisman and praised his Cuban ancestry, thanking his grandparents in Spanish. “Por el amor y sacrificio de mis padres y abuelos, los quiero mucho. De toda mi corazón, de toda gracias,” he said. The 2026 versions of the Breaking Away dad were left confounded, just as he was confused by Il Barbiere di Siviglia and fettuccine back in 1979. But like Italian heritage has normalized into the Americana melting pot, so too will the more recent emigres, despite current constraints and sentiments.

I see Breaking Away as more than a coming-of-age story for a singular individual, or even just a group of townies. Instead, it’s a coming-of-age story about a college and town becoming a college town. The backdrop is the rise of Indiana University. Beyond that, the film reflects changes in demographics, geography, economics, and educational growth nationally. Both Breaking Away then, and IU’s football team now, represent these constant changes in broader American society.

UPDATE: On January 20, 2026, the article was edited to show IU won the National Championship.

I was a High School senior when this came out and loved this movie. Thanks for reminding me of it, and yes I'm pulling for the Hoosiers tonight!

I saw this at the theater as a high school student and it has stuck with me so much ever since.

In fact, I met someone from Indiana recently and asked if she was aware of this movie, and thankfully she was.

It is a classic. Thank you for this!