Buying a Dying College Isn't a Real Estate Investment

The saga of Rider U and Westminster Choir College show the complications of dying colleges as real estate assets.

Christmas was in full swing in Princeton, New Jersey, when I visited Westminster Choir College (WCC) on a cold and grey late December day last year. Heading over to the campus from a quintessential walkable downtown, we passed houses decked out in lights, wreaths, and Santa decor, Main Street stores were packed to the brim with holiday shoppers, and we even bumped into a pack of carolers practicing in the park, readying for the big day.

The supposed dead choral college was in the middle of a bustling town, tucked into an affluent neighborhood, where the Christmas spirit was alive and well. Indeed, Westminster Choir College was not dead. Instead, the almost 100-year-old institution had been bought out by nearby Rider University in 1992, yet complications had long been brewing by the time of my visit.

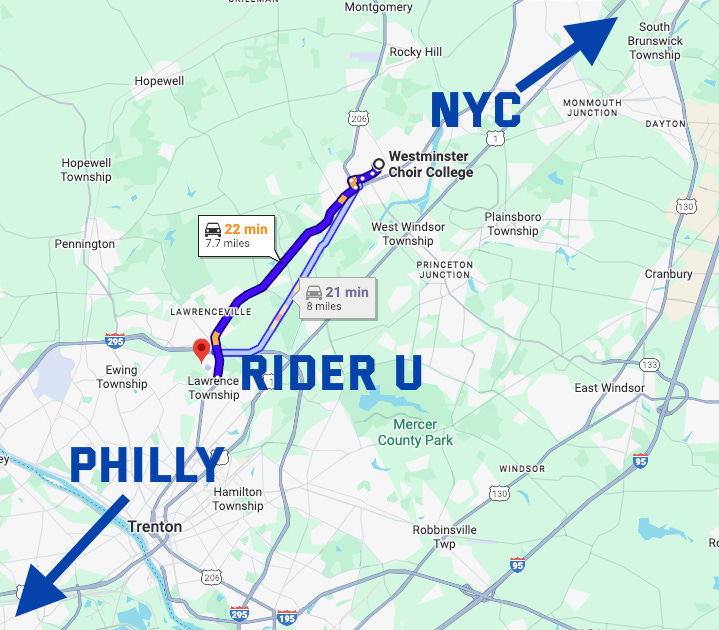

But after a few decades of marriage, the relationship between the couple was on the rocks. By 2020, Rider had moved almost all of WCC's programming to the main campus, roughly 20 minutes away in Lawrenceville. By the time COVID hit, Rider had already been struggling itself, with the pandemic only exacerbating issues. Divorce was imminent.

By April 2025, the separation was finalized. Rider kept the classes, programming, and history from WCC, but the Princeton Town Council took over the campus space. The town actually forced the sale through eminent domain.

The saga and my visit illustrate the tenuous relationship that can happen via a merger, especially one where one institution essentially acquires another that is dying. In particular, the rocky relationship shows that dead colleges cannot simply be viewed as real estate assets or investments. Yes, IPEDS labels campuses and structures as ‘assets’, but they are more complicated in the real world beyond the scope of real estate.

Troubles at Rider U

Last week, The Chronicle of Higher Education published an article entitled “After Rounds of Budget Cuts, Rider U. President Says It Was ‘Nowhere Near Enough’”, chronicling the downward spiral of the New Jersey university. Rider has made massive cuts recently and is under threat of losing its accreditation. Even with these reforms, the financial situation remains dire.

One part of the story that caught my attention was this claim:

Much of Rider’s financial woes trace back to its attempt to shed itself of Westminster Choir College, a small music conservatory in Princeton, N.J., it acquired in 1992. In 2017, administrators tried to sell the campus worth $40 million to a Chinese education-technology company and move the college’s programs to its main campus in Lawrenceville. Princeton Theological Seminary and advocates of Westminster sued, claiming the terms of the merger required that Westminster stay on the original campus.

The quote makes it seem like offloading the college was central to the university’s financial stability. Key to the claim was that Rider only received $13 million of the total $42 million due to a lawsuit filed by Princeton Theological Seminary regarding the initial agreement in 1992.

The Seminary believed that the original stipulations in the donation remained in effect from the 1930s, even in the handover to Rider in the 1990s. The courts agreed:

[I]n 1935 when philanthropist Sophia Strong Taylor donated the property to the choir college “to advance the training of ministers of music of evangelical churches,” according to the Mercer County Superior Court records. In Taylor’s stipulation, she specified that if WCC could no longer carry out her requirements, the title would be passed to Princeton Theological Seminary….

In 2018, the Princeton Theological Seminary sued Rider, claiming that once the university stopped operating a choir college on the land, the property should revert to the Seminary, per the wishes of the original donor of the land…

…To uphold Taylor’s terms, the agreement stated Rider must “preserve, promote, and enhance the existing missions, purposes, programs and traditions” of Westminster.

Despite the accusation that the acquisition accentuated the downward spiral, the WCC programs had reportedly operated with a surplus of $3 million per year as recently as 2017. Much of the programming had already long merged with the offerings at Rider’s main campus since 1992 under the College of Arts and Sciences. Over that span, Rider saw steady enrollments and peaked in 2009 at just over 6,000 students, as shown on Table 1.

The real problems began entering the 2010s, as Rider started seeing a steady decline in enrollment. The university ended the decade with just over 4,600 students in 2020, right before COVID decimated the sector. By 2023, enrollment had fallen even further to just over 4,000 students. The university had lost 2,000 students over this span, a third of its peak enrollment!

As I showed in a previous piece, US higher education hit peak enrollment at the exact time Rider did, with a slow and steady decline in the overall sector since then. Rider’s experience mirrors that of broader US higher ed. This means that the university had been growing for over a decade after acquiring the choral college. It was the Age of Conquest that doomed the Rider-WCC partnership, not the acquisition itself.

Contested Asset

If Rider’s purchase of WCC was a simple real estate asset, the university could just sell to the highest bidder. The campus, all of the buildings, and any other infrastructure were appraised at a little over $40 million. At one time, the president had even hoped that the sale could go as high as $60 million, which would have basically doubled the university’s endowment.

I could see the logic from higher ed administrators looking to trim the budget during lean times: keep the financially successful bits and shed the costly upkeep/maintenance of a satellite campus.

The problem with this kind of asset strategy is that campuses and colleges are not mere real estate. They come with expectations from the community about the buyers, lost (and found) history, and entitlement to the space. These concerns bring together a confluence of alumni, neighbors, and even politicians from the area.

Rider found all this out the hard way when it tried to sell the WCC campus to a Chinese company in 2017. Their announcement brought fury from these various stakeholders, arguing the sale to Beijing Kaiwen Education Technology Company (formerly Jiangsu Zhongtai Bridge Steel Structure Company) violated the original agreement. There were also concerns about a foreign entity with for-profit motives taking over the college.

During this time period, there was a wave of Chinese entities buying up colleges or educational institutions with varying success (or failure). One of those failures was Dowling College, in the next state over in New York, which has sat derelict for years after a similar purchase. I covered the community’s plight with the blight in a previous article.

After years of battling, the deal fell through in 2019. Rider decided, at that point, to pull all academic programs from the satellite Princeton campus to its main Lawrenceville campus. While the move upset some community members, there was never a chance to recover due to COVID in 2020. Likewise, the market for Chinese buyers dried up when the pandemic hit.

Christmas Choir and Community Connections

Moving WCC classes and academics out of Princeton did not mean that the campus sat empty. Rider had been leasing the space to local civic groups, such as Music Together, Princeton Pro Musica, and the Greater Princeton Youth Orchestra.

To its credit, Rider had also done a nice job of maintaining the space, as far as I could tell during my visit. I saw landscapers finishing up some work before heading out for the day. There was some initial construction happening under a sidewalk where pipes and wiring were being fixed. Given its financial burden, Rider could have neglected these kinds of things. They did not.

WCC remained a nice place even during rocky times. The campus was flanked by Princeton High School on one side and an affluent neighborhood on the other, which is, I am sure, one reason the protests against the Chinese purchase worked. This tucked-in old suburbia gave WCC a classic American small liberal arts campus vibe. This town-gown relationship was a good partnership, too.

The fenceless wide-open spaces were a clear third place for the local community. I saw loads of people running through and biking around, even though it was barely 30 degrees. I met one young fellow training his dog between campus buildings who told me he loved coming there. “I don't know anything about the college,” puzzled, he asked me, “Oh, it's not a choir college anymore?"

I guess I could see the confusion, since the signs of both Rider University and Westminster Choir College remained. There were also kids everywhere. And when I say kids, I don’t mean the way we call college students kids. I mean, actual children and their parents for Christmas recitals.

“Oh yeah, this one’s at 10, and the other one’s at 11,” a parent told me, who was waiting for their kid’s Christmas recital to begin. That particular day was Music-Fest’s Winter Carnival Recital, an organization with the following mission:

offers students and adult learners in central New Jersey an inspiring and collaborative weekly music experience. The program welcomes all instrumentalists, vocalists, and pianists. Our curriculum nurtures creativity, musicianship, and ensemble skills in a supportive, welcoming environment.

It has been reported that these programs will remain at this campus with the sale to the town. I am sure the dog walkers, runners, and parents are happy to keep their third place. Even the space that was still being used by the Westminster Conservatory, which is still a part of Rider University, may remain at the site for now.

Just because the investment of Westminster Choir College didn’t pay off for Rider University, doesn’t mean the asset is valueless. To the community, the space and campus are invaluable.

What Happens Next?

The sale of the WCC campus to the Princeton Town Council does not answer every question. The campus is still 23 acres with both old and new buildings in various states. While the recital and performance space was still in use and kept in good shape, there were questions in other parts of campus.

In some of the older buildings, there appeared to be offices that had not been used for a long time. There were also some dormitory or classroom spaces on another side of campus that looked from about the 1970s, which clearly did not have regular use. These kinds of spaces can quickly degrade, especially in the cold of New Jersey winters, piling up deferred maintenance costs. Rider seemingly kept the place looking nice, the town now takes over those duties.

The municipality has apparently hired a consultancy firm to help decide what to do with the campus. It is prime real estate in Princeton, but as Rider found out, the asset is limited. I do think the town itself likely understands the limitations. Some have suggested expanding the public school, public arts center, or even mixed-use developments (prepare for another bitter fight if for that last one!).

I cannot help but wonder why Princeton University does not swoop in to use part of the space at least. The campuses are only a 15-minute walk from each other. There is perhaps some inner working of both Princetons (the town and university) that I am not seeing.

In the end, the Westminster Choir College in Princeton, New Jersey, is no more. The ethos of the college is now wholly under Rider University within the College of Arts and Sciences in Lawrenceville. That space where WCC once sat for 80 years will live on, probably still holding onto some relation to music.

Unfortunately, like so many other institutions in US higher ed, Rider looks to be in some serious trouble. They are making massive cuts and the future is in question, as made clear by the Chronicle article. The lifeline that allowed Westminster Choir College to survive for over 30 years after it almost died in the 1990s may now be facing down its own demise. If it happens, the assets lost will be much greater than any real estate value.

Thank you for this -- it is heartbreaking. I threw my hat in the ring for the Rider presidency (an appropriate role for me as a former Dean of humanities in two universities who spent 12 years teaching at the Peabody Conservatory of Music) and did not even get a glance from the search committee, which got what it wanted -- a CPA MBA, not an leader of an institution of learning and the arts. When I saw who was hired it made sense, though sad sense. I did my PhD at Princeton, raised small children there. and have a sister who is a voice teacher in town still, who has spent innumerable hours at WCC. None of this had to happen but this is what happens when CPA MBAs look at institutions in terms of assets to be sold off.

A really thoughtful, nuanced essay.