US Higher Ed is in the Age of Conquest

Everyone is focused on the recent shrinkage, cuts, and closures but the backdrop of American higher ed has long been competition and expansion.

There have been a lot of headlines about cuts to higher education and colleges shuttering recently. It seems like every day there is some story about a university (or entire systems) cutting departments or programs. Likewise, every couple of weeks news breaks of an entire college closing for good.

It would seem, then, that US higher education is in an Age of Shrinking, but what is hidden in the cuts and closures is that it is not simply about contraction in the sector but competition. It is growing universities, new programs, branch campus, and generally expanding offerings. As Joshua Travis Brown describes the US higher education sector, it is a system hardwired for growth.

Under these conditions, the US higher education sector has been in the Age of Conquest.

Enrollment Arms Race

There has been a lot of discussion about the looming Enrollment Cliff in US higher education. The student recruitment pools will be missing hundreds of thousands of students who were never born in 2008, around the financial crisis. Stakeholders have been warning about this smaller cohort for years now.

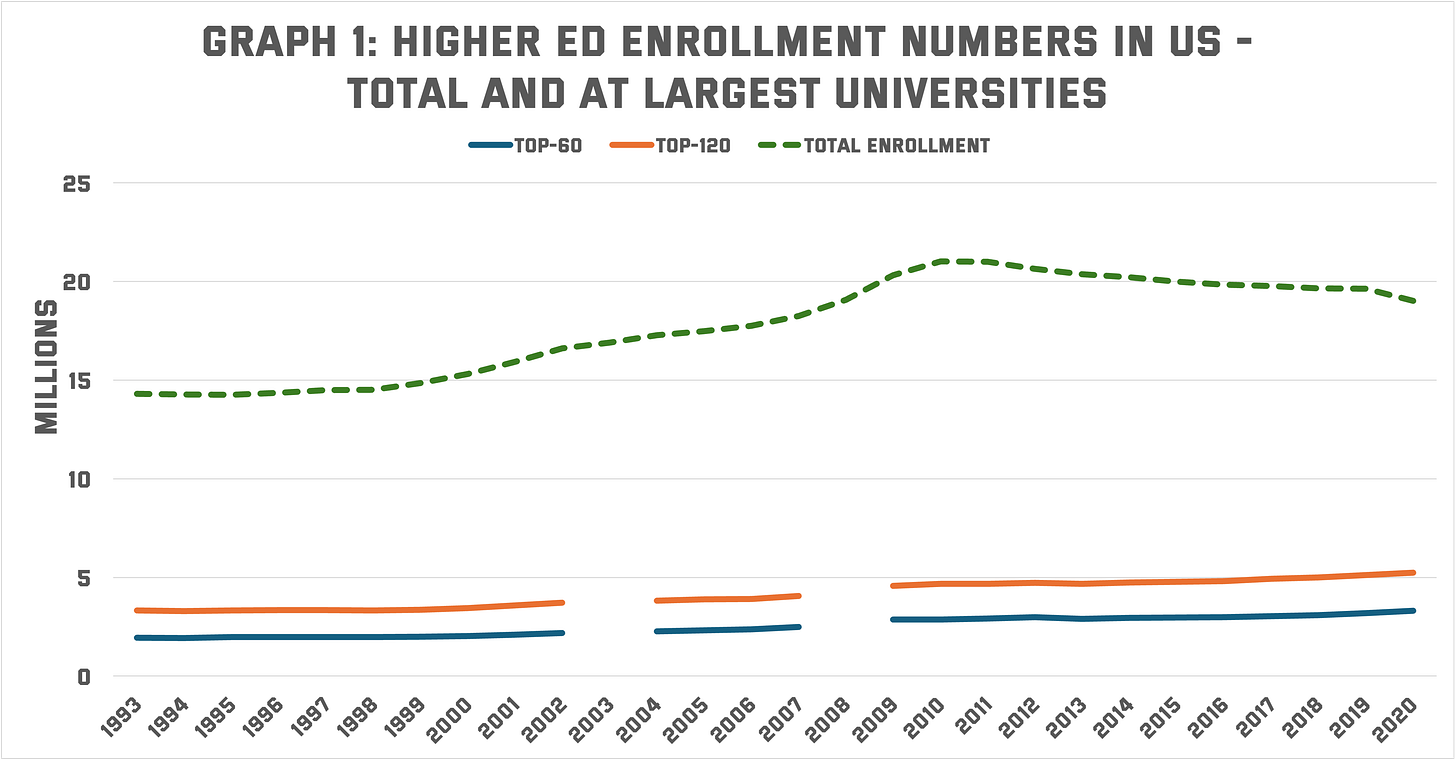

But what gets less attention is that higher education enrollment in the US already peaked. According to the National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES), the early 2010s saw the highest enrollment at just over 20 million students in US universities. It has ticked down ever since, and that is not even including the disastrous COVID era.

However, over the same time period that the US saw enrollment drop, the largest universities and colleges in the country saw their enrollment grow. The largest 120 institutions, a number tracked by NCES1, went from a little over 3 million students to over 5 million students. The same trend tracks with the top-60.

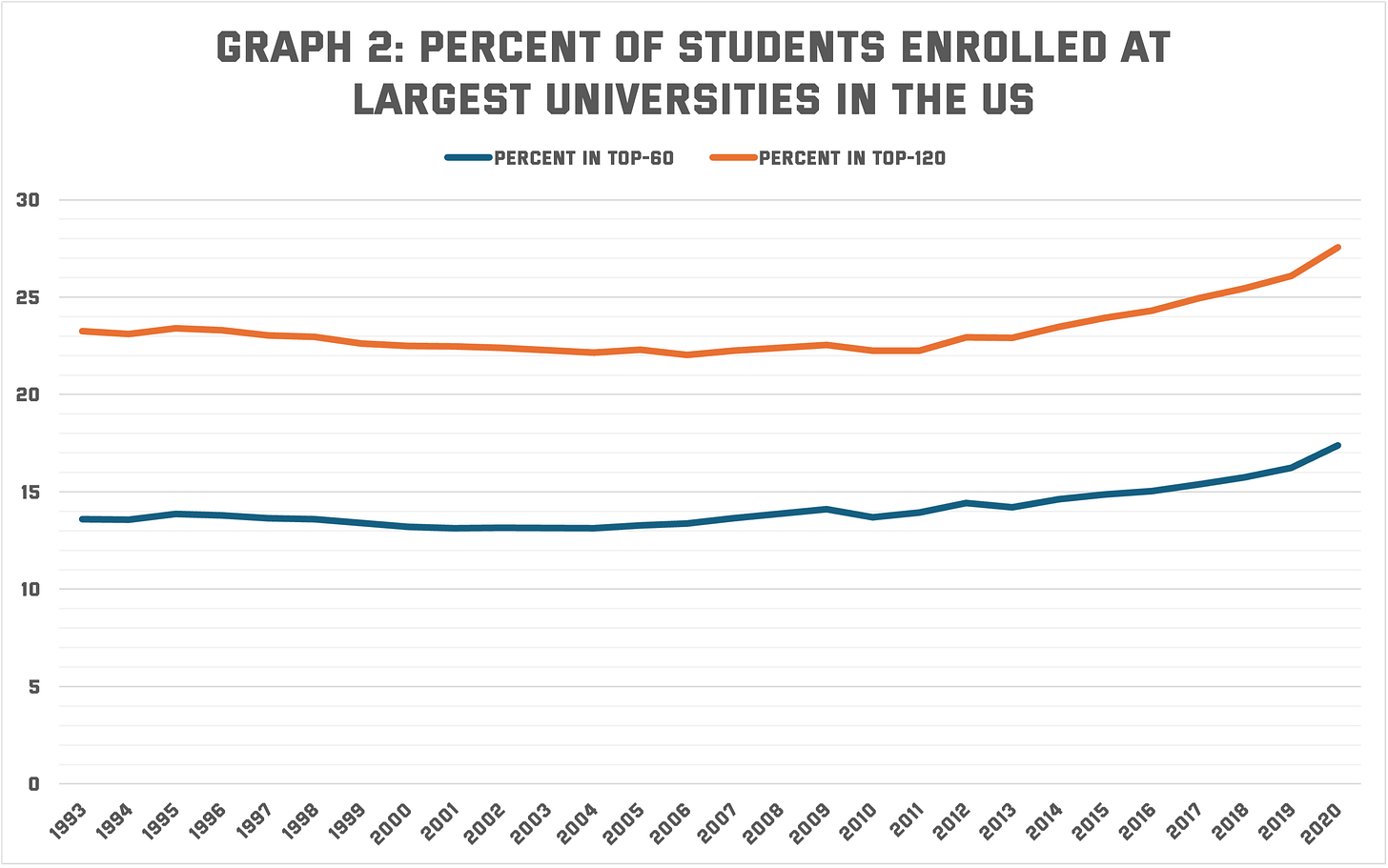

These numbers mean that, at the same time, the entire sector was dropping enrollment numbers, the biggest institutions were still steadily growing. Indeed, I tallied the percentage of students enrolled at these largest institutions and found that they increased their overall share during this period.

From the early 1990s until around the mid-2010s, the share mostly held steady for the top-120 and top-60 at roughly 22% and 13%, respectively. Beginning around when overall enrollment started to decline, these largest institutions saw their shares grow, up to over 27% and 17%.

In this era, the biggest institutions in the country not only grew in raw numbers but also in share of the dwindling student population. The NCES has been slow to release these top-120 numbers since 2020, but it is likely that the share for these biggest institutions has only gone up. Individual institutional data is available for recent years. Regardless, the pool of students has never reached the peak and is likely about to tumble.

The Biggest Get Bigger

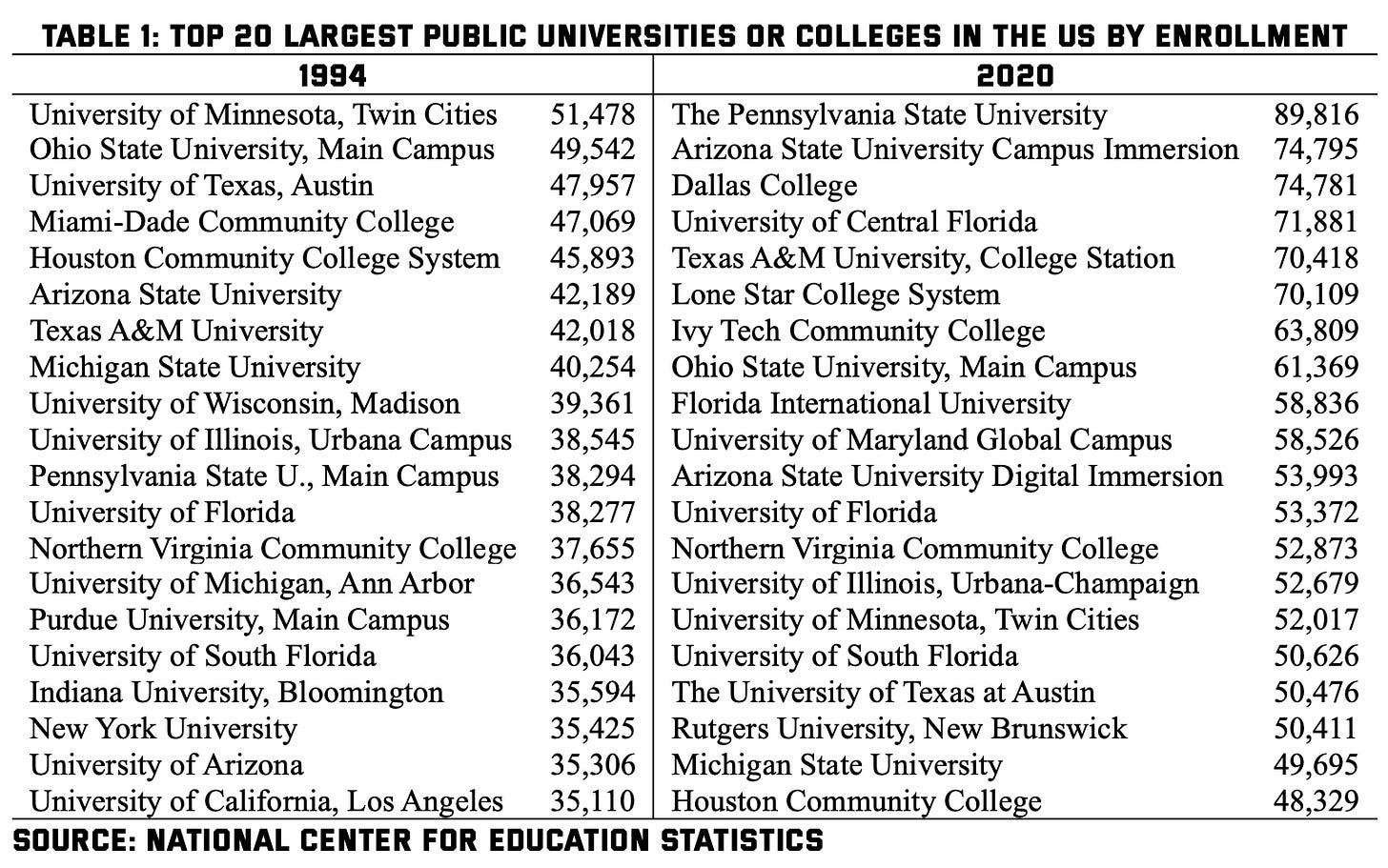

Many of the largest institutions come from the familiar flagship universities such as the Ohio States and Arizona States. These types of flagship institutions and land grant universities have long been massive. In the early 1990s, these places were already at the top of the largest institution charts, and many of the same universities remain there today.

Yet, the largest of these state flagships has been adding enrollment. In 1994, the largest of these flagships was the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, at just over 51,000 students. There were no others that eclipsed 50,000, and only four flagships at over 40,000.

By 2020, the largest flagship was Pennsylvania State University with almost 90,000 students, with several others over 70,000, and more over 50,000, eclipsing the 1994 largest. These growth rates for those at the top outpace the growth rates of the sector, as they now account for a larger share of the entire student population.

It was not just flagships growing; public community colleges swelled during this same era. In 1994, the largest community college in the country was Miami-Dade Community College at over 47,000 students. In 2000, Ivy Tech Community College in Indiana boasted over 63,000 students.

Furthermore, Dallas College and Lone Star College System are both listed as “4-year” institutions in the 2020 data, yet they were mostly offering 2-year community college programs. They both have over 70,000 students each. Given that they are now listed as 4-year institutions, these colleges have obviously added more programs over this span.

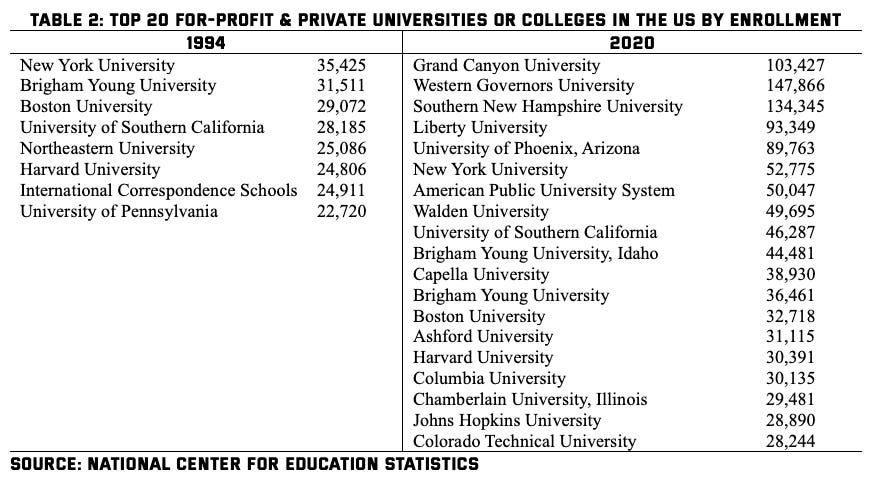

For-Profits & Global Campuses

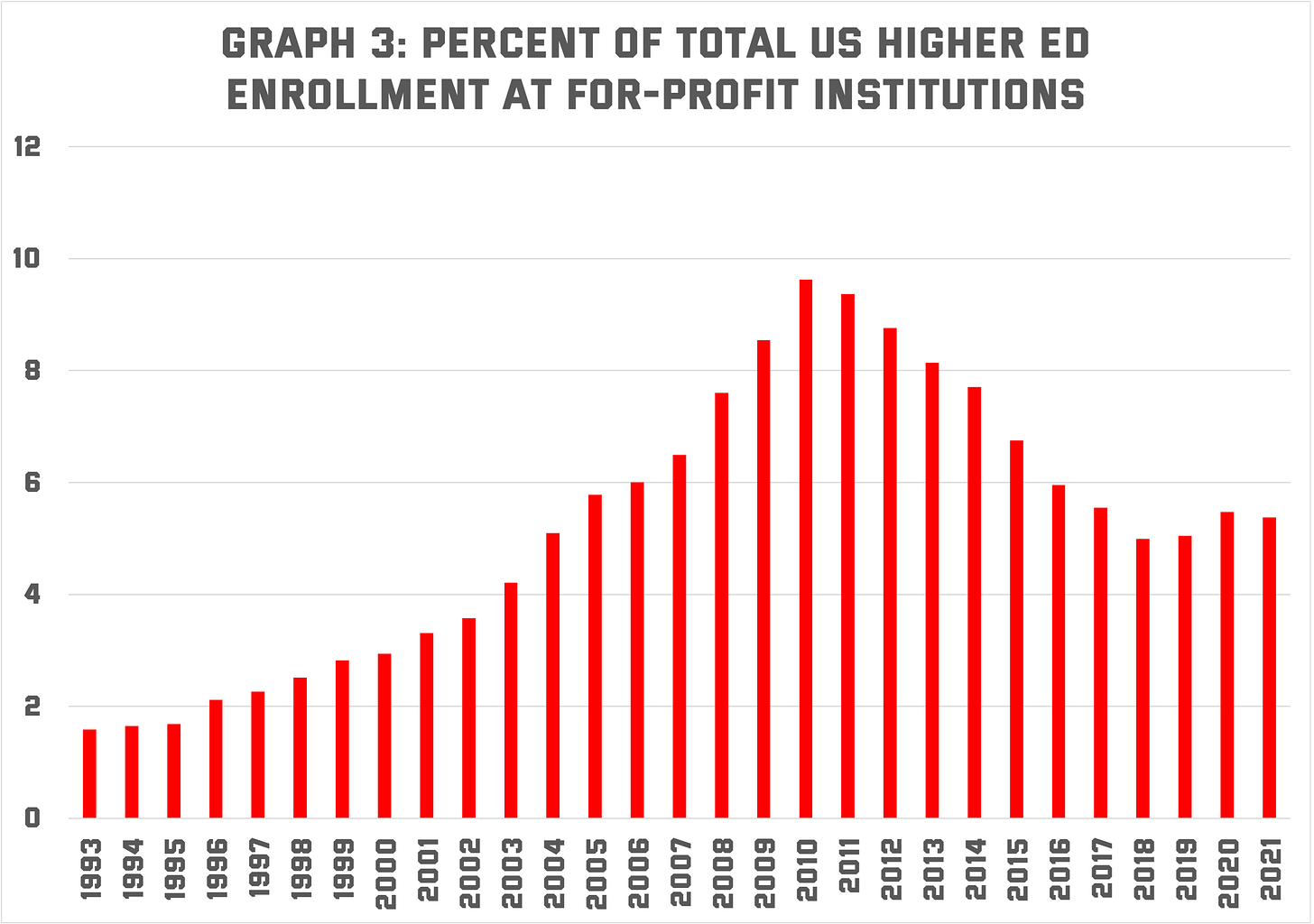

It could be forgiven that big state flagships and community colleges increasing enrollment is a public good. After all, they have explicit missions to serve their states. However, they were not the only ones growing over this period. For-profit institutions had massive gains during this area.

In the early 1990s, for-profit enrollment in higher education only accounted for roughly 1.5% of the sector. By 2010, this number was almost 10% of all student enrollment in the US. While this percentage did drop down to a little over 5% by 2020, the impact of for-profits has remained strong in the sector, especially for the largest of these institutions.

In the early 1990s, hardly any for-profits appeared on the top-120 list, with International Correspondence Schools at 67th place with a little under 25,000 students. As far as I could tell (NCES didn’t explicitly label for-profits then in this dataset), the rest of the list were public institutions.

As the years progress, for-profits become more common, especially during those late-2000s and early 2010 peaks. In 2020, though, there were 8 listed in the top-120. The largest should be familiar names, Grand Canyon University (GCU) and the University of Phoenix, with over 103 thousand and 89 thousand, respectively.2

These for-profits have pioneered growth through expansion of online programs, but they are also constantly in trouble for potentially shady business practices. Some have tried to go legit (e.g., becoming non-profits like GCU has been pursuing). Others have been bought out by large flagship systems.

Ashford University was listed as the 93rd largest institution in the country in 2020. In 2023, the University of Arizona bought Ashford, turning it into the University of Arizona Global Campus, a massive gain in enrollment for Arizona. Similarly, “Global Campuses” (aka for-profit brands) appear on the list with Purdue University, University of Maryland, and Arizona State University (ASU) under “Digital Immersion.”

These online brands are counted separately from the main campus by the NCES dataset. For instance, adding ASU’s Digital Immersion and Campus Immersion together would be a massive 128,000-student university.

These types of online expansions are a huge part of the Age of Conquest in US higher education. In fact, the top three institutions in 2020 are mostly online universities. Western Governors University with 147,000 students, Southern New Hampshire University at 134,000 and the aforementioned GCU.

Branching Beyond Geographic Boundaries

Online education can certainly reach beyond borders. But there is still an importance of geography for a university. Flagships are iconic symbols of states and even small liberal arts colleges are strong local symbols in college towns. But in the Age of Conquest in Higher Education, universities have been trying to break through these geographic constraints.

Colleges and universities have long had regional branches or centers, but they have usually been associated that were already in their sphere of influence. For instance, both Oklahoma State University (OSU) and the University of Oklahoma (OU) have branches in Tulsa, with the public flagships branching beyond their small college towns to serve the second-largest city in the state.

But top large private universities have also been growing rapidly during the Age of Conquest, sometimes perfecting the branch campus expansion strategy.

New York University is perhaps most famous for these types of branch campuses. They have high-profile campuses in Shanghai and Abu Dhabi. But they just opened a new study center in Tulsa, Oklahoma, adding another potential pipeline of student recruitment that competes with OU and OSU, along with other institutions in the area like the University of Tulsa.

Northeastern University has taken another tactic by buying up closing or struggling colleges. In this expansion push, the Boston-based university has annexed Marymount Manhattan College in New York, Mills College in California, and New College of the Humanities in the UK, adding to a range of other satellites.

The sector has only been seeing more of these acquisitions as colleges struggle, but at the same time, expansion of branches or centers into new locales by bigger institutions. ASU bought a site in Los Angeles for its film school. Vanderbilt University in Tennessee just made a substantial long-term investment into both a New York City-based campus and another Florida footprint.

These examples do not even include global expansion and programs. American universities have long looked to expand their footholds abroad. International students are certainly a part of this Age of Conquest. But institutions from around the world also now target the American sector. For instance, Imperial College London has plans for both a New York and California campus.

Bye Bye to the Little Guys

What the Age of Conquest means for American higher education is that the biggest and strongest schools only get bigger and stronger. The massive flagships are bursting at the seams with so many students that the institutions can barely house them, hence the rise of purpose-built student housing. The elite privates, at the same time, have plunging admissions rates in the single digits.

Community colleges have expanded access and programs, including to four-year degrees. Together with the for-profits and flagship “Global” brands, online offerings give reach to anyone, despite geographic limitations.

There is a trickle-up effect for all of this expansion that pulls students away from other institutions. Potential students who may have gone to one institution in the higher ed hierarchy end up going to another, slowly bleeding the smaller institutions of students.

Take Notre Dame College in Cleveland, Ohio, which closed in 2024. The small Catholic university had a peak enrollment of over 2,100 students in 2011, but by 2023, enrollment had dipped to less than 1,500. Over this same period, Ohio saw a 30% decline in higher education enrollment, a state particularly hit hard in terms of population decline. But some of the state’s leading institutions actually saw gains from 2011 to today:

Ohio State University: 56,867 ➜ 60,046

Miami University: 17,395 ➜ 18,618

University of Cincinnati: 33,329 ➜ 43,338

What this means is that a hypothetical student from Youngstown, Ohio, who may have opted for Notre Dame College in previous decades would instead go to the University of Cincinnati in recent years. Not to mention competition from the state next door with the massive Penn State, or more competition from the myriad of online providers.

Multiply this hypothetical across recruitment classes each year, and there just aren’t enough students to go around. These smaller places that are a bit quirky get crowded out. It is a shame because there are certainly students who don’t want to be at a massive flagship but who also want a traditional college experience. The broader drains have just become too insurmountable for many of these types of colleges.

Ohio and other depopulating states have already been facing these issues. But these same kinds of situations are happening across the country to varying degrees. The states that have already seen massive population drops portend the struggles coming for the rest of the sector with the looming Demographic Cliff.

Retreating from Conquest

The US higher education sector has long been defined by the Age of Conquest since the peak enrollment passed in the early 2010s. But there are signs that we may be entering a new era with the disappearing student pools. We may be entering the Age of Retreat, e.g. we expanded beyond the extent of sustainability and the pendulum is swinging back.

Cuts have been coming from across the board, even from the biggest universities and systems. Places that have ballooned enrollment and expanded program offerings over the last couple of decades are in retreat. Just this year, Texas A&M announced they would pause enrollment growth targets to so-called “rightsize” the institution.

Even though some places are still expanding geographic footprints, others are looking to refocus on the main campus. Middlebury College just announced the closure of its Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey, a West Coast outpost the East Coast liberal arts college acquired in 2005. Middlebury’s admissions rate this year was under 14%.

My guess is that we will see more things like this from the sector, a mix of pulling back from the Middleburys and continued expansion pushes by the Vanderbilts. The Trump administration only seems to be adding to the sector transition to a new age.

Nonetheless, whatever happens, there will likely be no reprieve for the small, quirky places that have already been struggling. The biggest in the sector will continue to dominate. The Age of Conquest may have just been a defense against the looming onslaught of the Demographic Cliff, bringing with it a new Age of Retreat for US higher education.

Update (9-8-2025): Fixed duplicate listing in table and added note about data.

Prior to the early 1990s, the NCES kept slightly different numbers such as top-100. Also, pre-1990s data is trapped in annoying PDFs rather than Excel sheets. Unlocking this old government data is a ripe area for AI actually (but that’s commentary for another article).

I just had to note that one with a hilarious name “American Public University System” is actually a for-profit institution.

"The Age of Conquest" is so dead on.

Agree. Definitely a system 'hardwired for growth'.

Sad to see an increased 'professionalization' of the university. Growing in numbers, but losing the essence of the university.

The liberal arts are so important now. Not just about $$.