Crisis by Design: Student Housing and the Hidden Cost of Higher Education

The rise of purpose-built student accommodations and commodification of studenthood in college towns.

Note: Today’s guest post comes from Shanshan Jiang-Brittan, Editor & External Relations Specialist at the Center for Studies in Higher Education, UC Berkeley. This essay in College Towns was adapted from a longer piece published in the Center’s Research and Occasional Papers Series (ROPS). The research shows how student housing has become big business. Important work. -Ryan

A recent University of Illinois graduate revealed that he left college with over $50,000 in student debt. But it wasn’t tuition that broke the bank. The student had a full scholarship. The burden came from housing: rents climbed to $2,000 a month in many off-campus apartments. The significant rent burden also reflects a national trend. A College Board publication showed that students at public four-year colleges in 2022–23 budgeted more for room and board than for tuition and fees.

This student housing crisis surrounding large public universities is a complex topic. The sector is not just impacted by strict local zoning laws or high land and construction costs, but also by multinational corporations entering the market. Off-campus housing has now been effectivity financialized and student living commodified.

The Rise of Purpose-Built Student Accommodations (PBSA)

From Berkeley to Chattanooga, Ann Arbor to Tallahassee, aesthetics inspired by global urban luxury are reshaping what it means to live as a student in the United States. Purpose-built student accommodation (PBSA) with features and services that go beyond the basic necessities now accounts for one-third of college housing nationwide.

The recent PBSA boom occurred despite a nationwide decline in college enrollment—from 21 million students in 2010 to 19 million in 2020. The paradox is explained by the uneven geography of enrollment. While small private and regional public institutions struggled to attract students, large public research universities continued to grow.

A key driver of the PBSA boom has been large public R1 universities. As state appropriations declined, especially after the 2008 financial crisis, many public universities increasingly turned to higher enrollment to make up for budget shortfalls. Between 2010 and 2021, 13 flagship public universities had over 20% enrollment growth, 14 had between 10-20% growth, and 11 experienced growths between 0-10%. Yet many of these institutions have not built enough housing to accommodate the increasing number of students. As a result, outsourcing student housing to the private sector has become a common strategy.

From Local Rentals to Global Portfolio

Unlike traditional rental housing, PBSA was designed for short-term, high-turnover tenants—allowing landlords to charge premium rents without long-term lease commitments. In recession times, such as 2007-08, student housing performed better compared to other real estate asset classes, partly due to the continued demand for higher education regardless of economics. By the mid-2010s, student housing had evolved from a niche asset into a full-fledged industry, with large-scale developers competing to build the most amenity-rich properties.

As the student housing sector matured, it drew the attention of institutional investors—including pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, and real estate investment trusts (REITs). In 2009, institutional investors and REITs accounted for 30% of all PBSA investments; by 2017, that share had grown to 67%. Major players include the State of Florida, Arizona State Retirement System, TH Real Estate, AIG, Liberty Mutual, and Principal Financial.1

Pension funds, in particular, have become the main source of global real estate investments. U.S. pension funds alone grew to $35 trillion in 2021, representing 62% of global pension assets. California’s CalPERS and CalSTRS are especially influential in the PBSA sector. A student in Michigan might never realize that their luxury apartment was partially funded by a retired teacher’s pension in California.

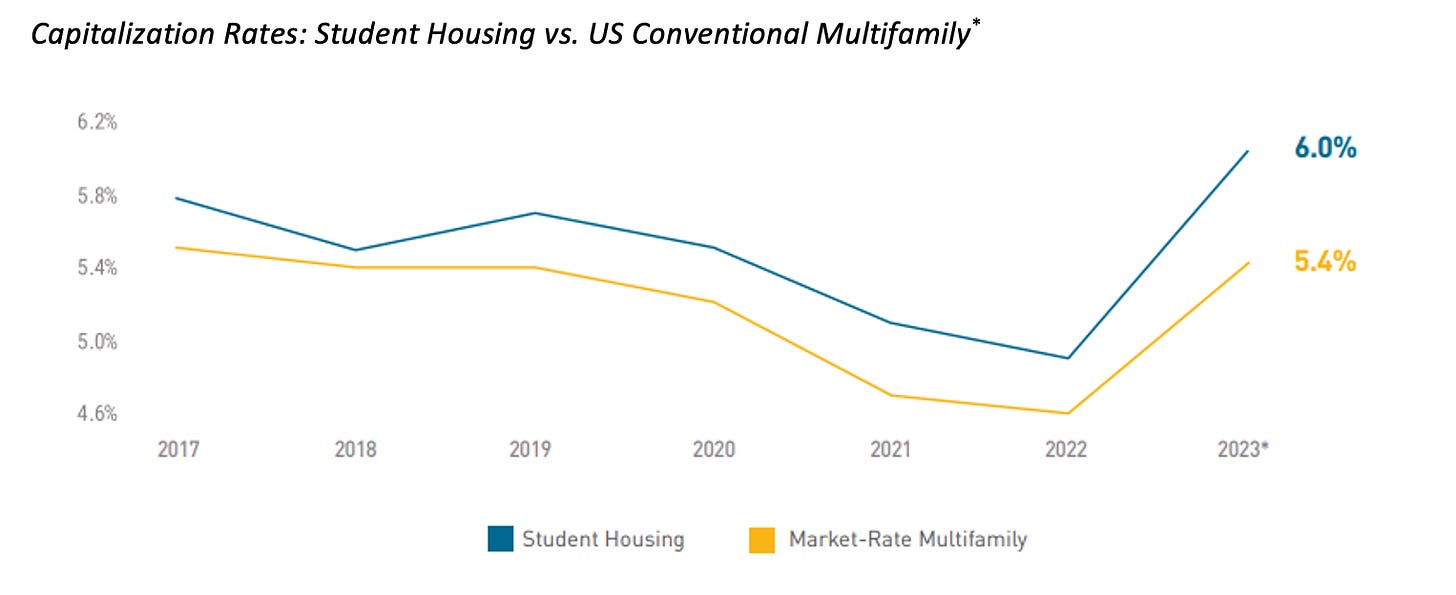

Foreign capital also plays a growing role in PBSA. In 2017, overseas investors were involved in 36% of all PBSA deals; by 2018, that rose to 42%. In 2018, a consortium including the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, Singapore’s GIC, and Scion Group acquired $1 billion in U.S. student housing properties. PBSA’s appeal lies in its higher returns compared to traditional multifamily properties and its lower delinquency risk.

Student housing also serves as a safe haven for foreign investors facing slow domestic markets. In 2019, Centaline Group, Hong Kong’s biggest property agency, co-invested in two student housing complexes near the University of Texas, San Antonio, and the University of Georgia. These properties were later sold at a $9 million profit margin. In 2023, Centaline returned with a $16 million investment into student property in Ohio to diversify while the Hong Kong real estate market struggles to recover from the pandemic-induced slowdown.

Commodification of Studenthood

This trend of financialization is what essentially distinguishes a new era of student housing. When student housing is treated primarily as a vehicle for financial return—or even as a symbol of global mobility—it becomes detached from the academic mission it is meant to support. While it may appear that students are exercising full agency in selecting where to live, their range of choices is structurally constrained. PBSA developments often occupy land that previously housed small businesses or independent housing options, effectively standardizing prime locations and displacing diverse local infrastructures. As a result, students are left with a narrower set of high-end housing choices.

In addition, by setting a new standard for amenities, PBSA developments contribute to an ultra-consumption culture in college towns, where luxury becomes normalized. PBSA creates a feedback loop in which each new luxury development raises the bar, prompting students and local housing markets to match the elevated standards just to keep up.

This commodification of college living is symptomatic of a deeper cultural shift: the commodification of studenthood. Universities and developers alike now often treat students not as learners, but as consumers—and sometimes, as products. Student rents are structured to deliver returns to investors, not to meet student needs. Reclaiming student housing as a public good and a core educational experience is not just about affordability. It is a necessary step toward restoring trust, equity, and sustainability in public higher education.

Note: You can find a longer and more in-depth version of this piece at the Center for Studies in Higher Education, UC Berkeley, Research and Occasional Papers Series (ROPS) website.

Capitalization rates are calculated by dividing the property's annual net operating income by its market value.

The rent gouging and lack of affordable housing near Universities is indeed a huge problem that brings an enormous additional cost to students as well as those working at Universities who don't have tenure or high salaries. Thanks for bringing this to attention

This is a super interesting post. Would be really interesting to see the extent to which the private housing costs exceed the cost of campus living, and to what extent this reflects markups, or differences in amenities. Consistent with this post, my university has seen an explosion in this kind of housing near campus, largely as a result of massive enrollment increases and modest expansion of university-run housing. But its not clear to me whether the high rents charged reflect higher amenity values, or students' lack of better nearby options.