Too Much Money in College Football? It’s Always Been America's Favorite Big Business

There are a lot of complaints about the money and changes happening in college football, but these same complaints could be heard throughout every era.

Certainly not more than three generations, each ethnic group has clicked into place in the union without losing the pluribus. When we read the line-up of a University of Notre Dame football team, call the ‘Fighting Irish,’ we do not find it ridiculous that the names are Polish, Slovak, Italian, or Fiji, for that matter. They are the Fighting Irish.

This quote is the opening chapter to John Steinbeck's lesser-known tome America and Americans (1966). The book itself is a celebration of the country and its people. The lead-up to this paragraph chronicles how different groups became “American.”

“Germans clotted for self-defense until the Irish took the resented place…”

“…The Irish became "Americans" against the Poles, the Slavs against the Italians.”

“…Chinese ceased to be enemies only when the Japanese arrived…

“…they in the face of the invasions of Hindus, Filipinos, and Mexicans.”

“…poor dirt farmers of Oklahoma… were met with perhaps even more suspicion and resentment than the other waves.”

In the end, these ethnic differences and divides washed away, according to Steinbeck, replaced by a collegiate sports team. College football, then, is front and center in how the popular conception of the country as a melting pot.

The sport is ingrained in what it means to be an American, which is why Americans love college football. This love is also why they hate to see it change.

The complaints about college football changing have been growing louder in recent years. Perhaps for good reason, as over the past few years, the sport has seemingly been undergoing a rapid and irrevocable transition. Players can get paid now… openly, teams have switched conferences… constantly, and there is now a high-profile playoff… playoffs!?.

Given its status in American culture, the amateur athletics competition is now a billion-dollar industry. Fans are struggling with the ballooning costs and the feeling that their beloved sport has become just another professional league. Fans now think there is just too much money in college football.

I am not here to say these changes aren’t happening. I am here to say that these changes have always been happening in college football. Since the early days and throughout its history, there has always been a belief that there is too much money in college football.

All About the Money… Since the 1940s

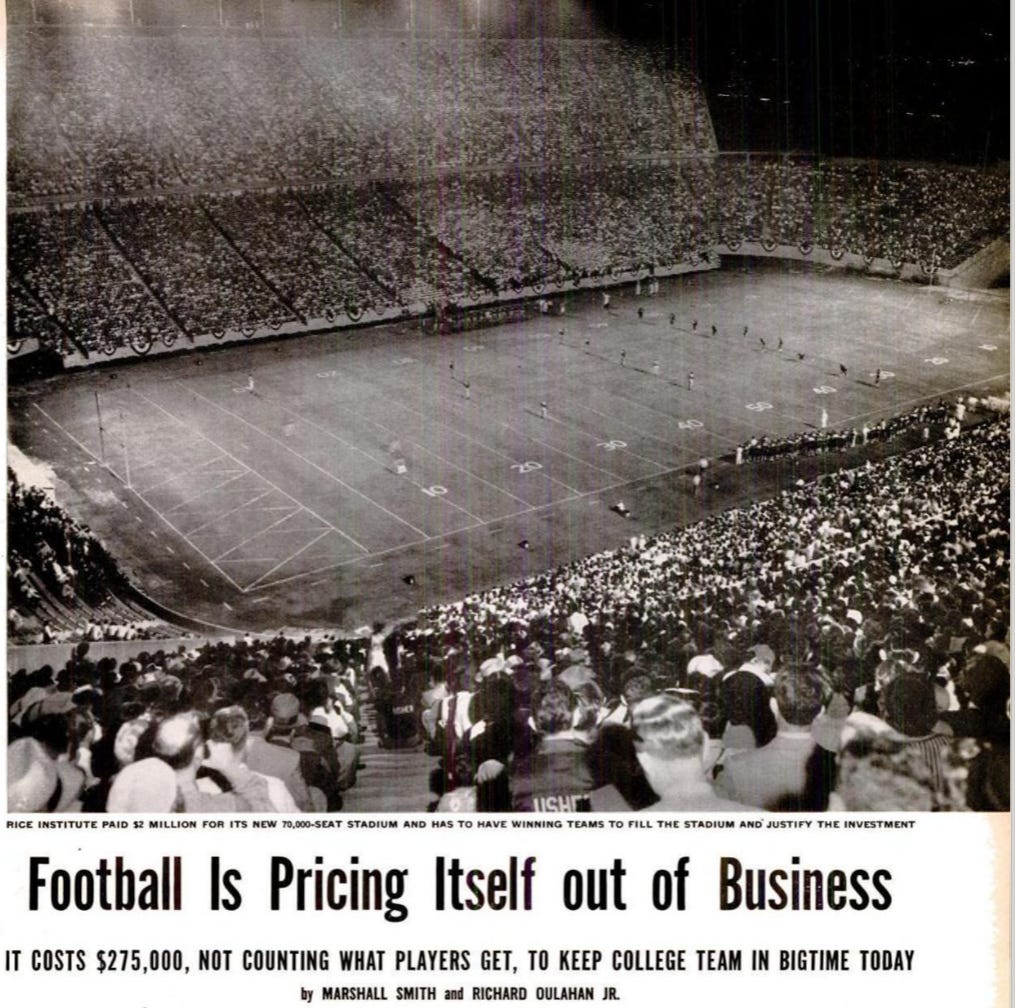

In an article from a Life magazine issue from 1950 entitled “Football Is Pricing Itself out of Business,” the authors Marshall Smith and Richard Oulahan Jr decry the changes that had been happening to the beloved game. They say everything was getting too expensive, players cost too much, coach salaries had grown exorbitant, it was no longer about the love of the game, and the big powerhouses were crowding out the small schools. Sound familiar?

The good old days, when any college could get rich simply by violating a few amateur ideals, are dead. Halfbacks can no longer be bought for $50 and a free education.

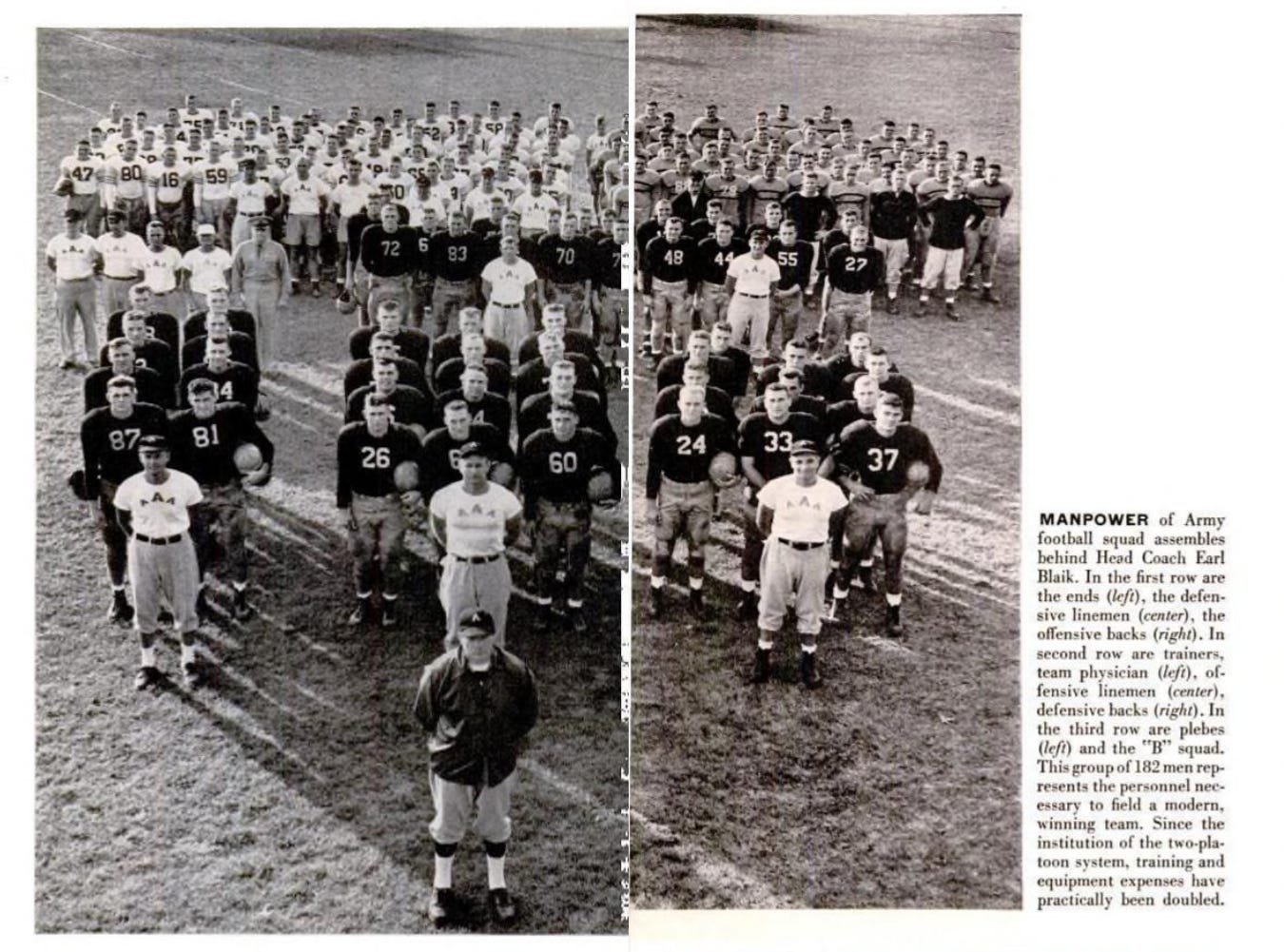

On the march of change then was the free substitution, which “bred the two-platoon system and the need for more manpower and more coaching power.” In today’s vernacular, this translates to the offense and defensive side of the ball. A change that has been taken for granted today (see, change isn’t all bad!).

One complaint that has not changed is that Notre Dame had an unfair advantage. The university has just consistently been a lightning rod of attention for the sport for over a century, including even today. In the 1940s and 1950s, even more so:

The big operators still have no worries. Notre Dame, which played to 59,000 cash customers in its opening game this season, was also watched by about six million more over a 46-station television hookup. Notre Dame gets $185,000 a season out of TV.

Of course, being from 75 years ago, there are some dated problems. My favorite part of the article is the report that when World War II ended, there was a rush to recruit the GIs to the colleges. The best part was, the GI Bill covered the cost of the education, but the schools had to get everything else.:

Since World War II the monster has grown bigger and greedier. The stampede for talent began on V-J Day with colleges bidding openly and without shame for football bodies. Ex-Gls who had played with service teams sat back waiting for offers, accepting deals that included shiny, new convertible cars and as much as $8,000 in the bank.

This sounds much like the college football transfer portal today, except rather than recruiting disgruntled players who didn’t get enough playing time for the Tennessee Volunteers, they were volunteers who went to fight Nazis. The Greatest Generation, indeed. Nonetheless, they, just like players today, wanted a piece of the big business then.

Another analog to the modern game was to the collectives that do much of the Name, Image, and Likeness (NIL) deals now. The college teams of the 1940s and 1950s were operating in a similar manner, even if at the edge of what was technically legal (or full-blown over the line). Smith and Oulahan Jr argued that much of the expenses were hidden because the largest line items of player subsidies were not included in the official university books.

Instead, the “player subsidy” was taken care of by alumni and donor groups:

“organizations like Educational Foundation, Inc., a group of loyal North Carolina alumni who maintain a fund of $500,000 and sweeten it by $150,000 each year.

“Ohio State has its Front Liners and Southern California its Trojan Club.”

“Oklahoma’s Quarterback Club dug deep in its pocket to buy talent last year.”

In one story, the authors tell of a fullback at Cal who bragged about his offensive line being “the best money could buy.” They also report that high school coaches were on “retainers” to steer “boys to the right campus.” To close the deal, recruits would get “$1,000 some happy alumnus slips into his pocket.”

Of course, even when all of this was happening in the 1940s and 1950s, some were clamoring for sanctions or suspensions. Carl Snavely, who was UNC’s coach at the time, admitted to the journalists that the violations were true. “I believe in declaring these players ineligible. The only way you’re going to control the alumni is to make them think their money is going to hell,” he said.

The coach, though, said he would continue to operate as such, that is until everyone else changed first. Game theory. Typical.

The rising costs meant schools were simply abandoning big-time college football. “St. Louis University, after losing $110,000 on football last year, abandoned the sport,” Smith and Oulahan Jr reported. “Canisius had a deficit of $70,000 and threw in the sponge. So did some smaller schools: Alliance, Steubenville, Portland U., Rollins, Oklahoma City University, Rio Grande, Genesee.”

Some “smaller” schools like Syracuse, Temple, and Boston College had even toyed with playing on Friday nights to avoid the bigger matchups. “The customers are staying away from smaller games to watch big ones on television. The little fellows are being squeezed out, and the big ones are getting bigger,” they closed.

While the sentiment was right, the prediction was wrong. The sport’s popularity only supercharged from the 1950s. And schools still fight for eyeballs on their games via TV deals, even playing on pretty much every day of the week like with what has become beloved MACtion.

TV Contracts and Conference Realignment

Those TV contracts seem to be part of what leads to so much consternation with the sport. It seems they are driving much of the commercialization, but this did not start with the streaming wars or even with ESPN. It goes back, as legendary coach Barry Switzer says, ‘half a hundred’ years ago.

In a 1971 Sports Illustrated issue, sports writer Pat Ryan penned an exposé on the sport with the ominous subheader: “After a Decade of High Living, College Football Faces a Serious Financial Squeeze. Costs Are Still Rising, but Revenues Approach a Ceiling. For All but the Richest Teams Austerity Measures Lie Ahead.”

During this time, college football was viewed as a bubble. Prices, costs, and resources simply could not go up forever. The ballooning was putting an unsustainable strain on not just the smaller colleges, but even the powerhouses. “In a sense, college football teams are like publicly held corporations. To keep the stockholders happy, each season must be bigger and better,” she wrote.

The bubble that was college football was about the burst:

In the '60s college football managed to stay generally abreast of escalating costs by upping ticket prices and cashing in on television. But now expenses are racing ahead of revenue… Many claim their ticket prices cannot be raised any more, which means their stadiums cannot be exploited further—they can only seat so many fans. Some major football schools have expanded their grandstands three times in the last decade. To make additions now would entail cantilevering the structure or massive excavating to build downward. The cost would be prohibitive.

Her analysis concluded that “Football's savior in the '60s was television,” but that the sport had already been oversaturated and there was little room to grow in the 1970s: “unlikely that TV money will be increasing.” Instead, there was a belief that the TV deals may contract in 1972.

These money concerns in the 1970s led to some of the same conference realignment that has defined college football over the last few years.

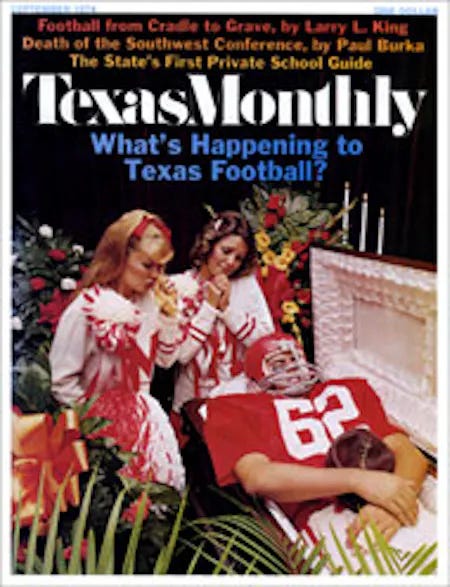

In 1974, Texas Monthly magazine’s cover mourned, “What’s Happening to Texas Football?” One of the lead articles chronicled the coming demise of the vaunted Southwest Conference. “The Southwest Conference is in trouble. Serious trouble,” journalist Paul Burka proclaimed.

Much of that trouble was rooted in the financial disparities between the colleges within the conference, namely, that of the University of Texas. Sound familiar?

One Longhorn athletic official puts it bluntly: ‘We’re subsidizing the conference,’ he says, and he reels off the figures. Every time a conference team goes to a bowl game, each conference school reaps more than $30,000. Every time a conference team appears on television the entire conference shares in the proceeds. The private schools haven’t gone to many bowl games recently, nor is the NCAA arranging its television schedule to get them more exposure on the tube—but they receive bowl and TV income nevertheless…1

Over its history, the conference had already seen a lot of movement, with colleges joining or leaving in the 1910s and 1920s, before stabilizing for a few decades. It also added Texas Tech in the 1950s and Houston in the 1970s.

When the article was written in the 1970s, it seemed like the Southwest Conference (SWC) was doomed, but it actually lasted another 20 years. The death knell came with the departure of Arkansas in the 1990s, leaving for the Southeastern Conference (SEC).

Soon after, core members of the SWC joined the Big Eight to form the Big 12, which expanded beyond its traditional tight geographic footprint. There are still a lot of older timers who look fondly at these SWC days of college football.

After a decade or so of stability, the Big 12 saw exits of major teams like Oklahoma and Texas chasing bigger TV money. Like the SWC nostalgia, I grew up in this previous era of Big 12 football that had more regional rivalries than the current iteration. My nostalgia is another fan’s annoying change.

These conference movements are just what happens in college football over the last 100 years. “The big ’uns will always eat the little ’uns,” quoted legendary Texas coach Darrell Royal in the 1970s piece. Indeed, from the doomed SWC to a reformed Big 12 and a powerhouse SEC, the cycle will continue, as it always has in the sport.

Paying the Players

Probably one of the biggest and apparent changes to the sport has been with paying the players. It does seem like the Wild West in terms of what is legal and what is allowable. I do admit there is a lot of confusion here.

But before the days of the NIL or transfer portals, these kinds of conversations were already happening around the sport.

In 1963, Sports Illustrated dedicated an issue to concerns over for commercialization of the sport. "I'm in favor of letting the professionals play pro football and the schools play amateur football," said Brigadier General John W. Dobson, who was a prominent player at Army in the 1930s.

There is a kind of faux nostalgia about what an amateur student athlete should mean. The vision is the Norman Rockwell illustration of the young man suiting up for the love of the game. In those pads, he became a hero. He probably really did love the game, but the reality is that even the hero was getting booster kickbacks.

Not every old timer believed they should just get paid in accoldates, too.

"Schools are getting involved in huge stadium investments, and to pay them off they have to draw crowds by fielding a winning team week after week,” said Dobson, who went on to lead efforts in the North Africa Campaign and invasion of Europe through Sicily in World War II. “If three-fourths of our big football factories were honest they would come right out and hire a football team to represent them.”

I don’t think a guy who survived being a POW in Nazi Germany is “soft” for wanting college players to get paid.

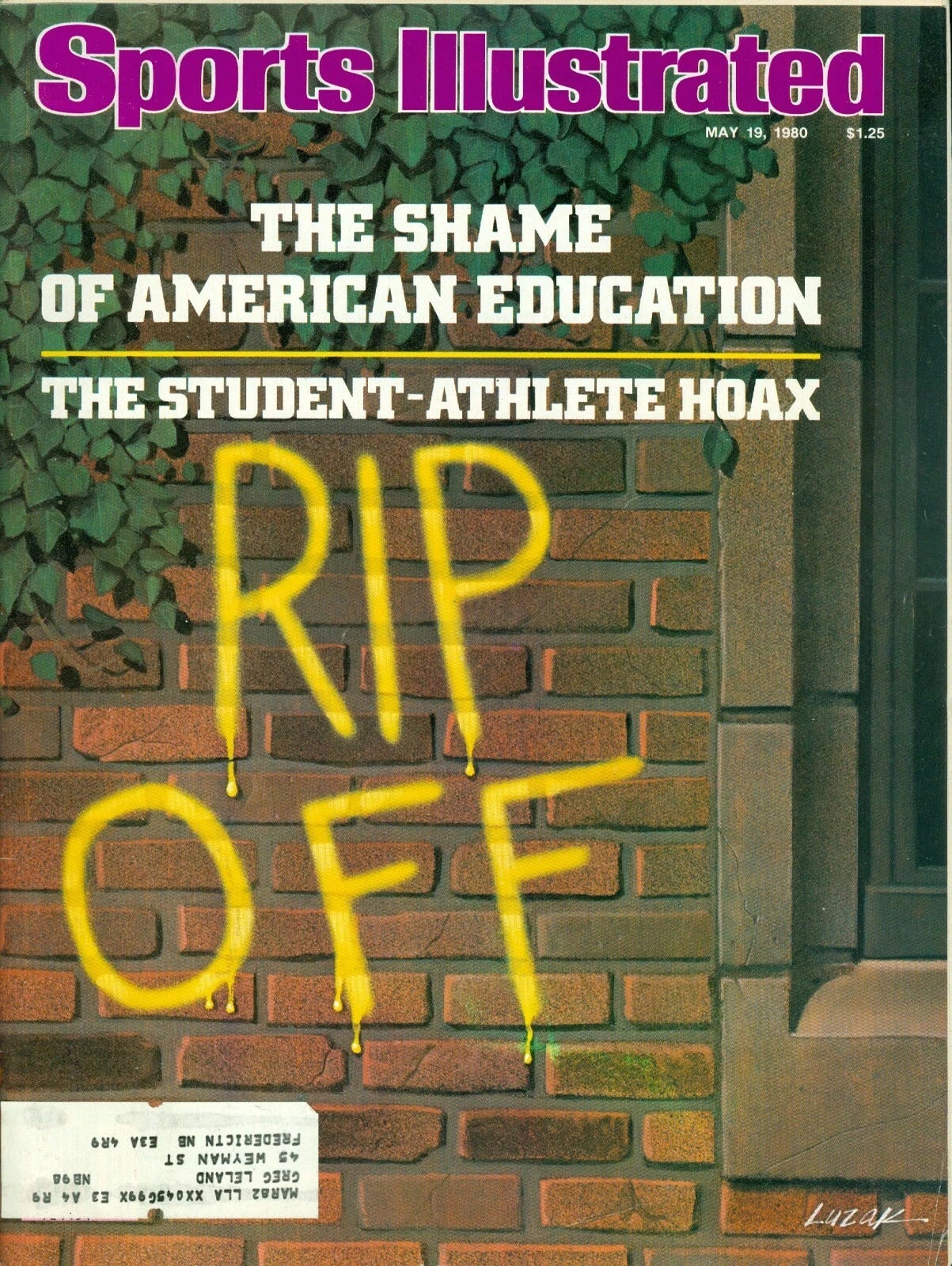

Nonetheless, these debates have continued. In 1980, Sports Illustrated questioned the entire foundation of college sports with a cover story: ‘The Shame of American Education: The Student Athlete Hoax.”

“Caught up in money-madness, they have made a legion of scavengers of their coaches—coaches desperate to win, desperate to get and keep in school those players who can help them win, and thus keep business booming,” wrote John Underwood.

In what is probably one of the most recognizable additions to these cultural debates, Blue Chips was released in 1994. While the movie centers on college basketball, the plot encompasses the entire premise of paying student-athletes.

In one of my favorite scenes, the big evil villain of the film makes a grandiose speech about paying players. In the end, the valiant coach admitted to wrongdoing to keep his old school morals. Only that those were not old school morals, but rather just idealized morals upheld as the truth; the reality was much greyer.

The One Thing Doesn’t Ever Change in College Football

Despite all of the changes in college football, people still love the sport. Each week, the biggest games rival most other sports in terms of ratings. EA Sports College Football 25 was the best-selling sports video game of all time. I certainly have fond memories of playing the editions back when I was in college in the 2000s.

College GameDay is still a cultural icon when ESPN brings the TV crew to town, even though Lee Corso retired this season. By the way, the GameDay college town visit only started in the 1990s, a relatively young tradition for a sport that boasts pagentry over a century old.

The show even created probably the most memorable interaction of college football last season, when Comedian Shane Gillis poked fun at recently retired coach Nick Saban by calling him “Alabama Jones.” The joke (and common sentiments within fandoms) was that now that everyone can pay their players, the SEC has lost its advantage (insinuating that they were long paying their players despite the regulations).

And I know there are still people who lament the erosion of the regular season and the irrelevance of bowl season. But I think we will eventually apperciate the playoff much like we simply take for granted the “two-platoon system.” It has to at least be better than a nerdy computer choosing two teams (sorry, BCS). Or several colleges just declaring themselves national champions (looking at you, Auburn). Right?

I do agree that the bowl system has gotten absurd. But this also isn’t new, either. I remember when bowls started getting ridiculous names like the Galleryfurniture.com Bowl or whatever sign the Dot-Com bubble was about to burst. That was over two decades ago now!

Even today, the Pop-Tarts Bowl is fun, even while absurd. They’ve created a new zany identity around it. I think it fits in nicely with the off-beat pageantry of college football, with the likes of an Old Brass Spittoon trophy between Indiana–Michigan State, Iowa’s pink locker rooms, or whatever happens at Texas A&M.

The entire sport is Americana. It is our national culture localized to individual college towns representing states and regions. This is why people care so much. Just remember, no matter which era was your favorite in college football, there was still concern then that there was too much money in the sport.

I thought this aside was funny: “Poor Baylor hasn’t won in half a century, since Calvin Coolidge was president. Baylor’s last championship was closer in time to Custer’s Last Stand than to us in 1974.” Always a good time to make fun of Baylor.

This is a great history, and context, thanks.

My takeaway though.. money has always been a part of college football (both overtly and covertly). But the sport was not defined by it, in the past. Now profit/money is priority one. College football is maybe a tragedy of financial escalation (?)

The attack on Researchers via cuts to their funding is at the heart of this fallen nations problems. Leadership of Universities all the way up to the highest office is under valuing science and over valuing things like college football. Billions are wasting on sport, at the expense of research. Money is a finite resource. The more spent on Football, the less for everyone else doing actual academic work.