College Towns, Strong Towns, YIMBY, NIMBY

The global business financialization of student housing illustrates complications between Strong Towns, YIMBYism, and NIMBYism in college towns.

College Towns recently published a piece by Shanshan Jiang-Brittan on the rise of massive private student housing developments near large universities. The piece illustrated how the increasing financialization of the sector was squeezing students. It caused quite a stir, with many comments supportive of the argument but others critical that it was using NIMBY-like logic.

In the comments, I defended the piece, but it got me thinking that a broader commentary on the topic was warranted. While my goal as the founder and editor of College Towns is not to always agree with everything a writer may post on the platform, I do largely agree with the assessment in Jiang-Brittan’s article.

YIMBY-Strong Towns Nuances

I consider myself a Strong Town’er first before YIMBY. I also basically agree with the broader YIMBY movement and think that they have been particularly important to moving us in the right direction in the state of California. Whenever I see Strong Towns’ Founder Charles Marohn argue with influential YIMBYs like M. Nolan Gray, it makes me uncomfortable. I should note that they cordially hashed it out on a recent podcast.

For a long time, I used to think that the differences were mostly semantic and didn’t matter in the grand scheme of things. There was so much in common that the fringes could be hashed out once we actually made meaningful progress. But the piece on the financialization of student housing did illustrate some of the potential real divisions in the movement.

The Strong Towns ideal is wary of those giant mega projects, preferring instead small incremental bets to build up housing stock and thicken up places incrementally. Massive housing developments backed by global investment firms necessitate massive financialization.

Marohn’s most recent book, Escaping the Housing Trap, co-written with Daniel Herriges, is all about the ills from this financialization aspect that has come to dominate the US housing market:

The large players that dominate the homebuilding industry today will not. Their business model relies on economies of scale, standardization of design elements, and streamlined finance… In many local housing markets, these large players constitute an effective oligopoly: a small number of producers who collectively enjoy price-setting power due to limited competition. Think of airlines or broadband Internet companies as classic examples of how oligopolies lead to high prices and poor service.

A college campus does not fully equate to a regular city, yet the same principles largely apply. These giant developments popping up across college towns across the country cost hundreds of millions of dollars to build. They then get traded and passed around by global firms for their investment portfolios.

What ends up happening is a monoculture of housing supply. This standardization of large-scale projects and limited ownership is uneasy for the Strong Towns movement. In this case, saying housing is housing sits uneasily with the Strong Town approach in these college towns.

Crowding Out the Little Guys

In an interview with Dave Deek on Governance.fyi, I said that NIMBYs were not the enemy: “I think rather than saying the enemy is NIMBYs, I think the enemy is freezing our towns in amber and endless sprawl.”

A key reason why college towns have been seeing these massive developments is because of local restrictions that attempt exactly this: to freeze the town in amber. In a highly restrictive market with endless community engagements, an obstacle course of red tape, and other add-on costs, only the most affluent companies can afford to run the race.

The little guys cannot afford to wait seven years to build something. They will simply exit the market, and they have. When they do sink all this time and energy into just getting the building built, then it necessitates a massive block in order to recoup investment.

“But the immediate postwar era was the last gasp for the swarm. Since then, the development business has consolidated. There are fewer builders than ever, but they work at larger scales than ever,” wrote Herriges in a Strong Towns piece. “Urban land costs have skyrocketed, requiring larger projects to turn a profit. Wall Street exercises unprecedented influence in what gets built where.”

Student Housing Gone Corporate

The private student housing sector has become increasingly corporate because it is such a lucrative space. The large-scale student housing providers have consolidated around the market in these towns. There is little locality when the owner of the dorm is a multinational corporate office based in an offshore tax haven.

Blackstone has even admitted that local supply constrictions have been key reasons for its investment in student housing. “Simply because there is more demand for housing than there is supply of it. As a country, we are probably about four million units shy of where we should be by now based on household formation growth,” said the company’s global co-head of real estate, Kathleen McCarthy, to CNBC.

Every week, I see companies trading multimillion-dollar student housing real estate in college towns across the world like Pokémon cards. For instance, Campus Advantage promises investors huge returns on their student housing portfolio due to growth and unmet demand. They stated, “annual sales volume increasing over 200% in a five-year period from approximately $2.95 billion in rolling average in 2013-2014 to $6.12 billion rolling average in 2018-2019.”

Even the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board and Singapore Sovereign Wealth Fund have gotten into the student housing game. GIC, which runs the Singaporean fund, owned a sizable holding of $568 million investments in the student before selling it to Greystar for $1.6 billion in 2024. Retirees around the world are building their wealth on local student struggles.

However, these companies did not create the conditions. And I do not blame them for what has happened in many college towns. These firms are merely taking advantage of conditions that have been set on the ground locally.

NIMBY College Towns

I don’t want to paint the big corporations as evil and the small landlords as angels. It is not simply black and white. Small-time landowners have squeezed students, too; some are even working with the big corporate providers.

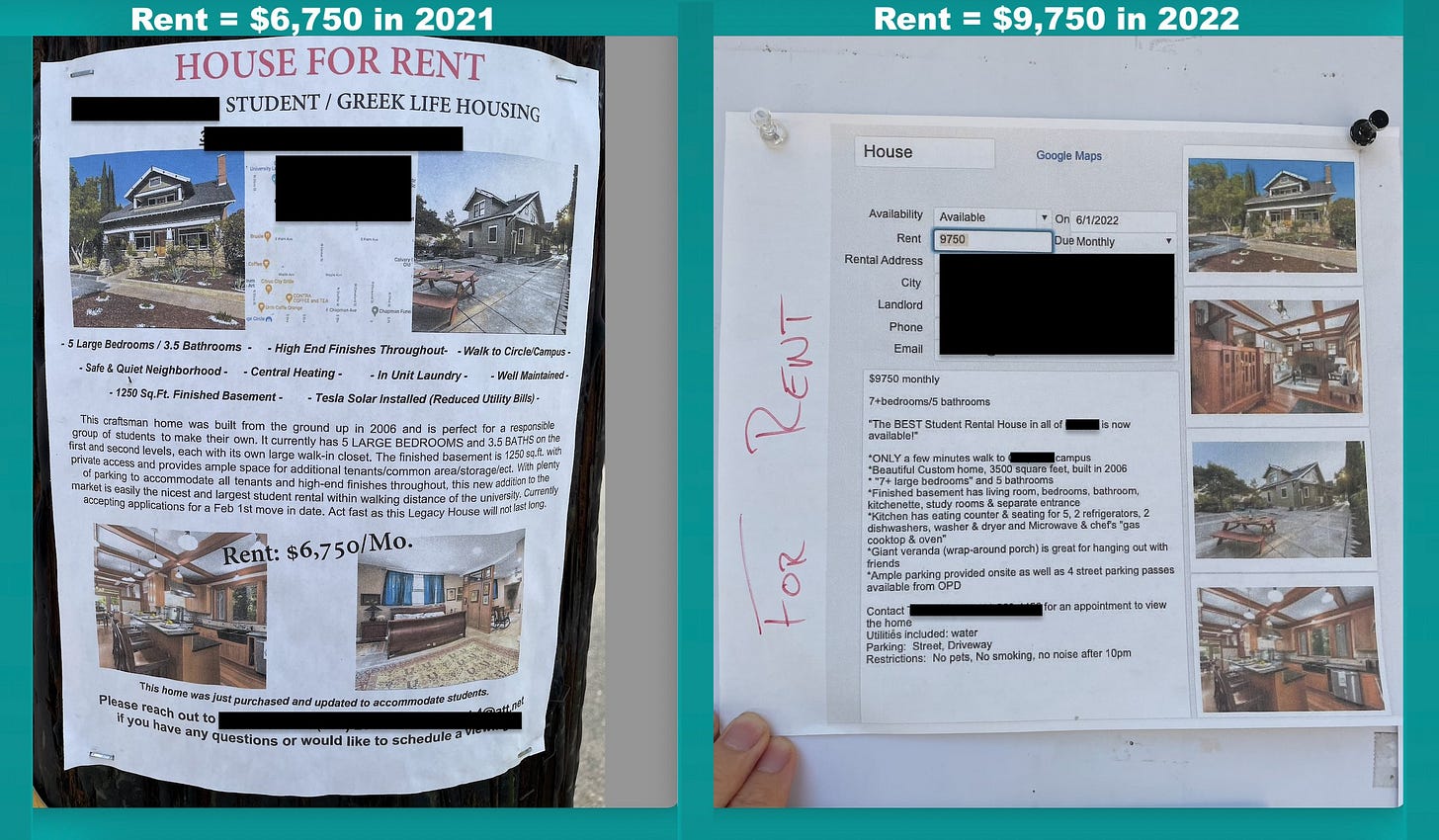

For years, locals have been happy to limit development to the campus and limit supply around the town. While the numbers back me up, I have also seen firsthand the massive rent spikes in my little college town.

In my former college town around Chapman University, the town of Orange put strict zoning restrictions on multifamily units in the late 1980s. The ones that survive are quite desirable for students and young people. But they are few and far between, which pushes students to outer cities like Anaheim.

Further up the state, the city of Berkeley, home of UC Berkeley (or Cal for football fans), pioneered some of the strictest zoning laws in the nation. Not necessarily to target students initially, "City attorney separately characterized Berkeley’s zoning proposal as part of a broader California tradition of segregating away ‘heathen Chinese,’” wrote M. Nolan Gray in Arbitrary Lines.

Eventually, though, strict zoning laws had adverse effects on students as the college outgrew its old boundaries and dorms. Similar stories happened around so many colleges. Rather than trying to build more units, some localities put limits on how many unrelated people could legally live in a house (aka Brothel Laws).

Some college towns have finally been pushing back in terms of housing reforms. Places like Fayetteville, Berkeley, Gainesville, and Ann Arbor have all made progress in various ways. The state of Texas, too, just banned Brothel Laws in certain college towns this year. I would love to hear how these types of laws are even constitutional (but that is for another article).

The restrictionists in these places who help keep the supply of student housing artificially low create conditions for landlords to squeeze students, whether that’s Blackstone, Canadian pensioners, or the local guy who rents out his parents’ house but now lives in a McMansion in a nearby affluent suburb. The Blackstones, though, don’t vote in local elections, nor do they protest other small-scale developments like ADUs or duplexes.

Tower Defense

I do want to add some nuance to this discussion on the types of housing in college towns. I do not think the giant private student dorms are all bad. In fact, they do bring up some good that should be considered.

Most importantly, they add much-needed housing stock. Even if it is not my ideal type or aesthetic, they are still rooms and beds for people to live in. And certainly, some students do prefer to live in these types of developments because they have top-notch amenities like gyms or pools. They can be easier to rent for students compared to normal apartments (especially important for international students).

It’s also not always simple for universities to build more dorms. Raising the finances can be cumbersome. Likewise, there are politics involved in how, why, and where to build dorms. For instance, at UCLA, the UC Regents argued that a proposed dorm was too small despite the rooms being the same dimensions as other campus housing.

Further, when a university buys property off campus, the city loses tax revenue because universities are non-profits. College towns often have massive budget shortfalls because of this (which will be a future article by me here).

So many students face some kind of housing struggle that living in a car or crashing on a couch for a semester is all too common. Long Beach City College even created a policy whereby students could sleep in their cars in the campus parking garage.

Simply put, we need more housing, and college towns need more student housing. In short, they are fun places to live, like luxury dorms. Not everyone wants to live on campus or in a scummy fraternity house (which is what I did).

An Ideal Mix of Housing

Despite the global land grab for student housing, these are local problems that demand local solutions. Banning Greystar, one of the country’s largest student housing owners and funders, from building massive towers isn’t going to fix our college towns.

In a vacuum, building these massive student dorms can be a good thing. If the choice were just to build these massive private dorms or build nothing, I would choose the giant dorms every time. They are housing for students who need housing, which is a YIMBY Abundance-type message.

The problem comes from the standardization of the sector in a specific college town. Because of the restrictions and highly financialized market, the fictionalized vacuum hypothetical becomes the reality choice.

There has been a strong NIMBYism within college towns for decades. The townspeople sometimes do not appreciate the college students they live with, hence the town vs. gown dynamic. The Town is often angry at the college for growing enrollment, and would like to keep the town frozen in amber.

I want a mix of housing stock. Some big luxury towers for our pampered students, noisy frat houses on Greek Row, an ADU behind a professor’s house, a mid-rise apartment built in the ‘60s before they were banned, and a lot of on-campus housing for everyone.

This is the ideal mix, but it should be just that, a mix. It is bad for the town when one single entity comes to dominate the housing market with one single type. That is true for just the college or big private dorm development.

Universities themselves are not passive audiences, they should be active players. Obviously, they should build more housing, but they should consider smaller developments. Things like like BOXABL could be experimental options.

Another thing is that they cannot appease locals with on-campus housing. The land that the university owns and operates should be geared towards the needs of students. Freezing the campus in amber cannot be an option, nor should thinking about height issues or setbacks. It helps to sell these developments to skeptics if they are at least good-looking (another future article).

Finally, college leaders need to embrace communities trying to build housing, not just the massive developments, but also the smaller firms. The people building ADUs, townhouses, and duplexes around town are just as important as the Blackstones of the world.

It will not happen overnight, but neither did the land grab of global investment firms in dorm beds around the campus. Universities are local, and they can and should be part of the bottom-up revolution to make our places better. We cannot simply blame outsiders.

Correction: Aug. 7, 2025, a photo of UC Berkeley was misattributed as UCLA.